A new wave of research has raised the bar on how we understand and classify obesity in the United States. Until now, many clinicians and public-health authorities have relied on body mass index (BMI) as the primary threshold for obesity. But a recent global expert commission and a large U.S. cohort study suggest that this measure alone may miss many people at risk. When the new criteria are applied, nearly 70 % of U.S. adults meet the definition of obesity, far higher than the traditional figure. This article unpacks what has changed, why the numbers leap up, and what the implications might be for individuals and health systems.

What changed in the definition

The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology Commission published in January 2025 a revamped framework that defines obesity not solely by a BMI threshold but by excess adiposity, fat mass, and its consequences. Under the new system, obesity is diagnosed when there is excess body fat and signs of organ or physiological dysfunction (clinical obesity) or when excess fat is present but function is still preserved (pre-clinical obesity). The new criteria also emphasise anthropometric measures such as waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio or waist-to-height ratio, and, where available, imaging of fat mass. This change reflects an effort to align diagnosis with measurable organ and metabolic risk rather than weight alone, and to prompt appropriate, evidence-based interventions when risk is present. Clinicians and researchers argue that the goal is better targeting of care and prevention, not stigma.

Key U.S. study findings

In a large U.S. cohort study, the new definition was applied to over 300,000 adults drawn from the All of US Research Program and other data sources. Under the traditional BMI-based criteria, about 42.9 % met the obesity threshold; under the new multidimensional definition, about 68.6 % met it. The increase was largely driven by people whose BMI fell below traditional obesity cut-offs but whose fat distribution or body-composition indicators placed them in higher-risk categories. This suggests that many previously classified as “not obese” may nonetheless carry an elevated risk of metabolic disease.

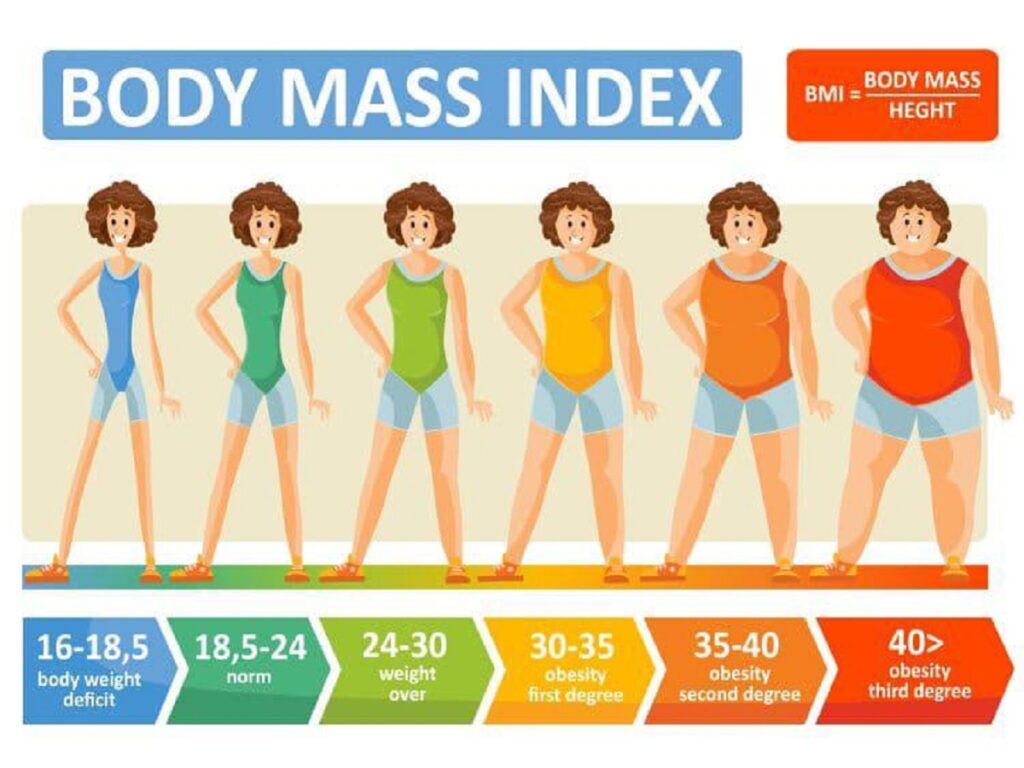

Why BMI alone falls short

BMI calculates weight relative to height (kg/m²) but makes no distinction between muscle and fat, nor does it indicate where fat is distributed. Someone may have a “normal” BMI but carry excess abdominal fat (sometimes called “normal-weight obesity”), or a raised waist-to-height ratio beyond thresholds tied to cardiometabolic risk. The new criteria emphasise those anthropometric and body-composition measures because central (visceral) fat is a stronger predictor of conditions such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The shift seeks to improve the identification of individuals who are at risk, even though their BMI appears unremarkable.

Who gains and who loses under the new rules

The application of the new definition alters who is classified as obese. Older adults, men, and some ethnic groups (especially Asian individuals at lower BMI thresholds) showed the biggest relative increases in prevalence under the new criteria. At the same time, individuals who met BMI-based obesity but lacked elevated fat distribution measures or organ impairment may now fall into the “pre-clinical” rather than “clinical” category, which could influence whether they receive certain therapies or insurance coverage. The net effect is shifting thresholds and shifting populations, not simply more of the same.

Clinical vs pre-clinical obesity

The new framework distinguishes between pre-clinical obesity (excess adiposity with maintained organ and tissue function) and clinical obesity (excess adiposity with demonstrable dysfunction in tissues, organs, or metabolic pathways). The idea is to stratify care: those in pre-clinical stages may receive lifestyle counselling and monitoring, while clinical obesity may warrant more aggressive intervention, medications, structured programmes, perhaps surgery, depending on evidence of harm. This staging aims for precision in treatment rather than a one-size-fits-all label.

Health-outcome evidence

In the U.S. study, individuals who were newly classified under the updated criteria (i.e., those with adverse anthropometric markers but previously normal BMI) demonstrated significantly higher risks of metabolic disorders compared to those who did not meet any obesity criteria. That suggests the new definition is not simply enlarging the label of obesity but capturing meaningful health risk. It means earlier identification may open doors for prevention, but also challenges in broad-based clinical resourcing as more people qualify for risk-based monitoring and intervention.

Public-health implications

If nearly 70 % of U.S. adults fall under the obesity category as per the new definition, this vastly alters population prevalence and could change our benchmark for progress. Public-health programmes would need to recalibrate screening, prevention messaging, funding, and tracking. With such a high figure, prioritising resource allocation becomes tougher: should every newly classified person receive the same level of care as someone with a BMI ≥ 30 previously? Policymakers must consider the cost, benefit, and feasibility of scaling up interventions while avoiding diluting efforts for high-risk individuals.

Practical challenges in implementation

Translating the new definition into practice has hurdles. Measuring waist-to-height ratio, waist-to-hip ratio, or doing imaging scans (DXA or other fat-mass assessments) is more time- and resource-intensive than BMI alone. Many primary-care settings may lack standardised protocols for these measures, and insurers may not yet recognise them as diagnostic. Equity concerns also arise: communities with fewer resources may struggle to access advanced diagnostics or structured care pathways, risking widening disparities rather than closing gaps.

Communication, stigma, and care

Broadening the definition of obesity risks amplifies stigma if messages are not carefully framed. The Lancet Commission emphasises treating obesity as a chronic condition requiring evidence-based care rather than moral judgement or blame. Health systems should pair diagnostic upgrades with patient-centred education, supportive programmes, and emphasis on function and health rather than simply weight. The success of the new approach will depend as much on how it is communicated and delivered as on how it is defined.

Next steps and unresolved questions

Despite the promise of a more accurate definition, it is not yet universally adopted. Validation in diverse global populations, cost-effectiveness studies, threshold-setting (how many anthropometric markers qualify), and alignment with policy and insurance are still in progress. Clinicians and researchers must decide how to integrate the new criteria into practice: which patients to treat more aggressively, how to monitor those in pre-clinical stages, and how to avoid over-medicalisation. The leap to ~70 % prevalence underscores urgency, but it also underscores the need for measured, equitable implementation.

Comments