The 1960s were a moment in history when culture, technology, and social norms were shifting at a remarkable speed. Many everyday habits from that decade seem astonishing today, not because people were reckless, but because society simply didn’t yet understand the risks. As science progressed and public awareness grew, a number of once-ordinary practices were gradually outlawed for safety, health, or ethical reasons. Looking back at these now-banned norms offers a glimpse into how far we have come and how the rules shaping daily life continue to evolve with each new generation.

1. Smoking on Airplanes

Smoking aboard commercial flights was once so ordinary that many airlines offered complimentary cigarette packs with meal service. Cabins had “smoking sections,” though the ventilation systems ensured smoke drifted everywhere, coating seats and recirculating through the air. By the late 1980s, mounting research on secondhand smoke pushed regulators to restrict the practice, and by the mid-1990s, most airlines had banned it entirely. The shift marked a major public-health victory, transforming flying into a cleaner and safer experience for passengers and crew who once had no choice but to inhale lingering clouds at 30,000 feet.

2. Lead-Based Household Paint

Lead-based paint was widely used in the 1960s because it dried quickly, resisted moisture, and produced vibrant colors that homeowners loved. It was marketed as durable and reliable, and few questioned its safety until studies revealed how lead dust from peeling walls caused severe developmental and neurological issues in children. As the evidence became undeniable, governments stepped in, and by the late 1970s, most countries had banned its sale for residential use. The decision reshaped home-safety standards and introduced stricter rules on renovation practices, especially in older buildings where remnants of the toxic paint still linger.

3. Asbestos in Home Construction

In the ’60s, asbestos was considered a kind of miracle material because it resisted fire, insulated well, and strengthened countless building products. It appeared in everything from floor tiles to attic insulation, and builders relied on it without hesitation. However, long-term studies uncovered a devastating link between asbestos fibers and life-threatening illnesses such as mesothelioma and asbestosis. As public concern grew, regulations tightened, eventually outlawing most uses by the late twentieth century. Today, specialized teams handle asbestos removal, reflecting how dramatically attitudes toward once-trusted construction materials have changed in just a few decades.

4. Riding in Cars Without Seatbelts

During the 1960s, seatbelts were optional in many vehicles and rarely used even when installed. Families often squeezed into front benches or let children stand while the car moved, believing accidents were unlikely and speed limits kept roads safe. Rising crash data exposed the deadly consequences of unsecured passengers, pushing car makers to adopt safer designs and governments to mandate seatbelt laws through the 1970s and 1980s. What once seemed unnecessary evolved into a life-saving habit, drastically reducing fatalities and reshaping how people think about basic road safety every time they step into a vehicle.

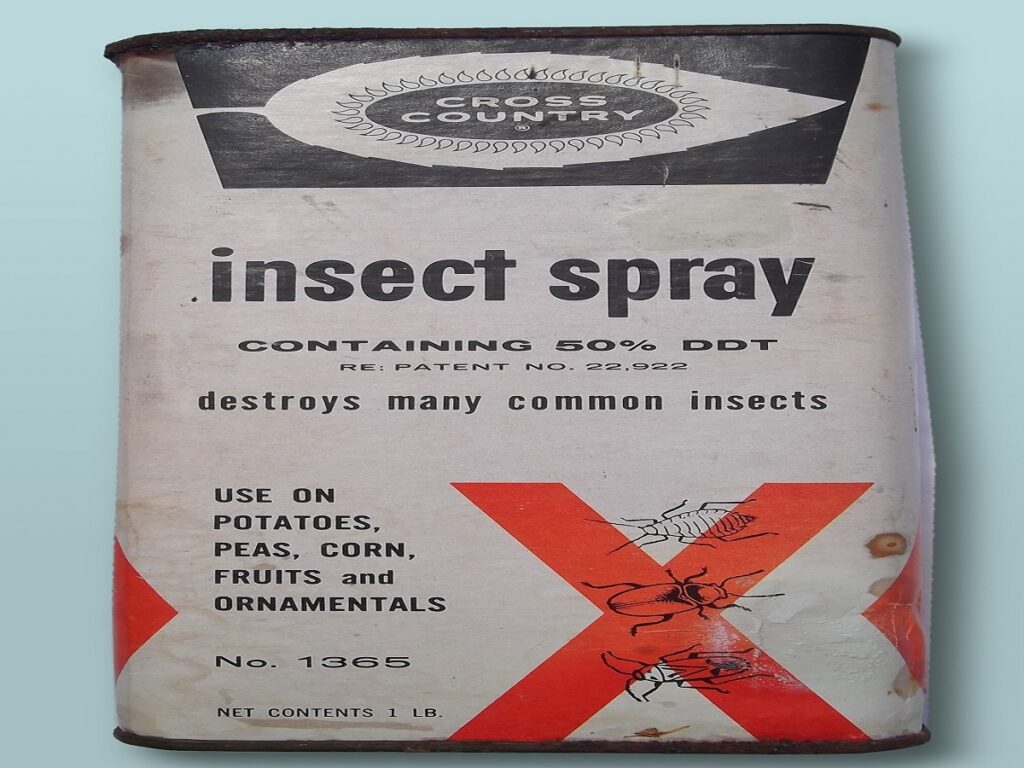

5. Using DDT as a Household Insect Killer

DDT was celebrated in the mid-twentieth century for its ability to eliminate pests quickly, and homeowners frequently sprayed it around kitchens, gardens, and play areas. Its widespread use seemed harmless until research uncovered its long-lasting environmental impact, including severe harm to birds and contamination of soil and water. By the early 1970s, mounting ecological damage led many countries to ban the chemical, sparking major conversations about responsible pesticide use. The DDT ban became a turning point in environmental policy, reminding the public that convenience can come at a much higher ecological cost.

6. Allowing Kids to Roam Without Supervision

In the 1960s, children often spent entire days outside with no adult in sight, wandering through fields, riding bikes across town, or exploring nearby woods. Parents trusted communities to watch over them, and society viewed independence as an important part of childhood. However, growing awareness of child safety concerns and shifting cultural expectations gradually changed these norms. By the 1990s, unsupervised play became heavily restricted, and laws in some regions now classify it as neglect. While some argue the shift reduced risk, others believe it narrowed opportunities for freedom once enjoyed by earlier generations.

7. Advertising Cigarettes to Kids

Bright cartoon mascots and catchy jingles made cigarettes seem fun and harmless, and tobacco companies in the 1960s freely marketed to young audiences without facing ethical scrutiny. As health research expanded, it became undeniable that early exposure increased lifelong addiction and severe medical risks. Public pressure mounted, prompting governments to introduce strict advertising bans through the 1970s and 1980s. These rules reshaped media standards and dismantled decades of targeted marketing. Today, such ads are not only illegal but almost unthinkable, reflecting a broad cultural shift in how society views corporate responsibility toward children.

8. Playing with Mercury in Classrooms

Many 1960s science classes treated liquid mercury as a fascinating toy, letting students roll the shimmering metal between their fingers during simple experiments. Teachers believed it posed minimal danger, unaware of the long-term neurological effects associated with even small exposures. As research revealed the seriousness of mercury toxicity, schools quickly phased it out, replacing those hands-on demonstrations with safer alternatives. Strict disposal rules were later followed, ensuring the substance would no longer be casually handled by children. The ban highlights how scientific understanding continues to reshape even the most familiar learning environments.

9. Driving After “Just a Few Drinks”

Social drinking culture in the ’60s treated driving after alcohol as normal as long as someone didn’t appear visibly drunk. Bars often had parking lots full of patrons who intended to drive home after several rounds. As accident statistics and medical research exposed alcohol’s impact on coordination and reaction time, lawmakers introduced stricter limits and intensified enforcement. The shift transformed public attitudes, turning a once-casual behavior into a serious offense. Modern campaigns, checkpoints, and ride services now reflect an understanding that impaired driving endangers not only the driver but everyone on the road.

Comments