Human fascination with life after death has existed across cultures for millennia. The afterlife, a realm beyond our physical existence, is interpreted differently around the globe. From serene paradises to cyclical reincarnations, each culture envisions a world shaped by morality, ritual, and spiritual essence. Exploring these diverse beliefs offers not only a glimpse into human creativity but also a deeper understanding of values and fears across civilizations. Here are ten unique perspectives on what might await us after death.

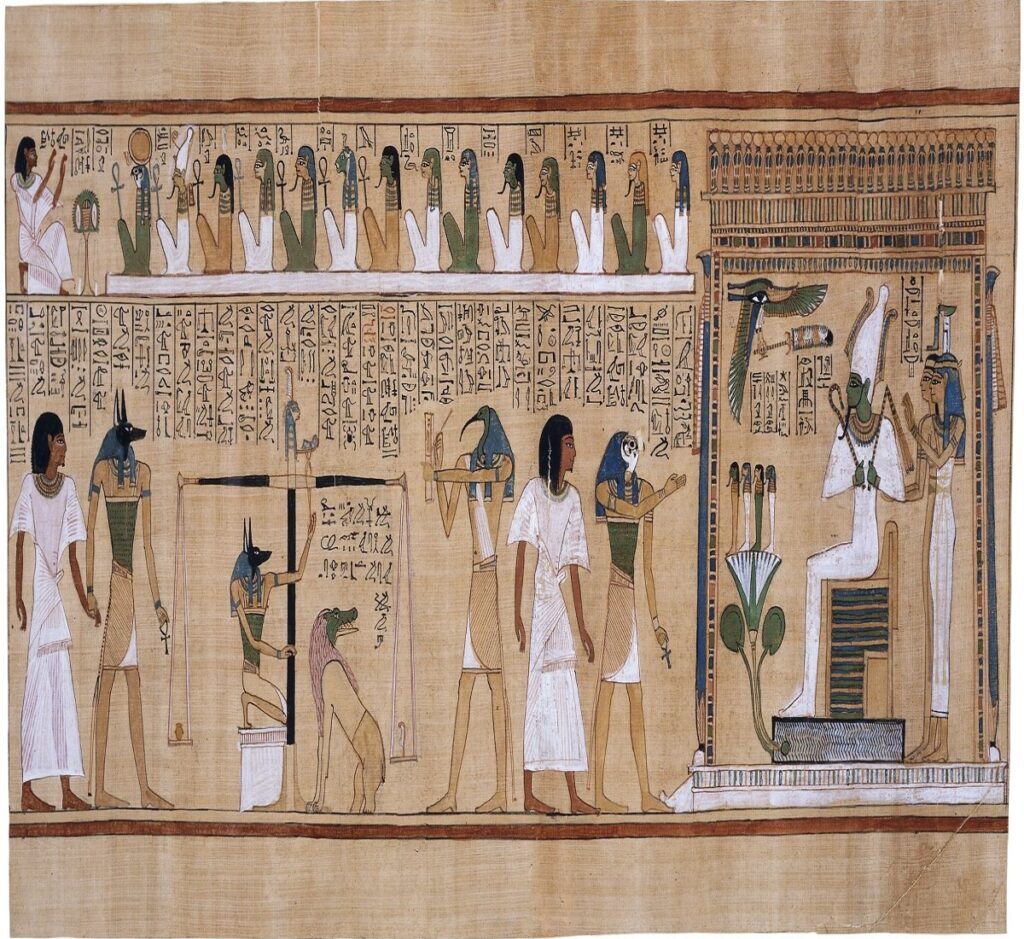

1. Ancient Egyptian Duat

The ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife called the Duat, a complex underworld where souls underwent judgment. Dating back to around 3000 BCE, this belief centered on the “Weighing of the Heart,” where a deceased person’s heart was measured against the feather of Ma’at, representing truth and balance. A heart heavier than the feather indicated a life of sin, resulting in destruction, while a balanced heart allowed entry into eternal bliss. Elaborate tombs, mummification, and funerary texts like the Book of the Dead reflect the immense importance Egyptians placed on navigating the Duat successfully.

2. Tibetan Bardo

In Tibetan Buddhism, the Bardo is an intermediate state between death and rebirth, believed to last up to 49 days. Developed around the 8th century CE, this concept guides souls through a transitional period where consciousness experiences visions and encounters karmic consequences. Rituals such as reading the “Bardo Thodol” (Tibetan Book of the Dead) aim to guide the deceased toward a favorable rebirth or liberation from the cycle of samsara. The Bardo emphasizes the fluid nature of existence and the power of the mind in determining one’s journey beyond death.

3. Norse Hel

Norse mythology presents Hel, an underworld realm ruled by the goddess of the same name, where most souls go after death. Originating in pre-Christian Scandinavia around the 9th century CE, Hel was neither wholly pleasant nor entirely punitive. The honorable dead often reached Valhalla or Folkvangr, but Hel was reserved for those who died of illness or old age. The realm was imagined as cold and shadowy, yet structured with specific regions. This belief reflected the Norse understanding of life’s unpredictability and the moral neutrality of death, emphasizing legacy and valor during life.

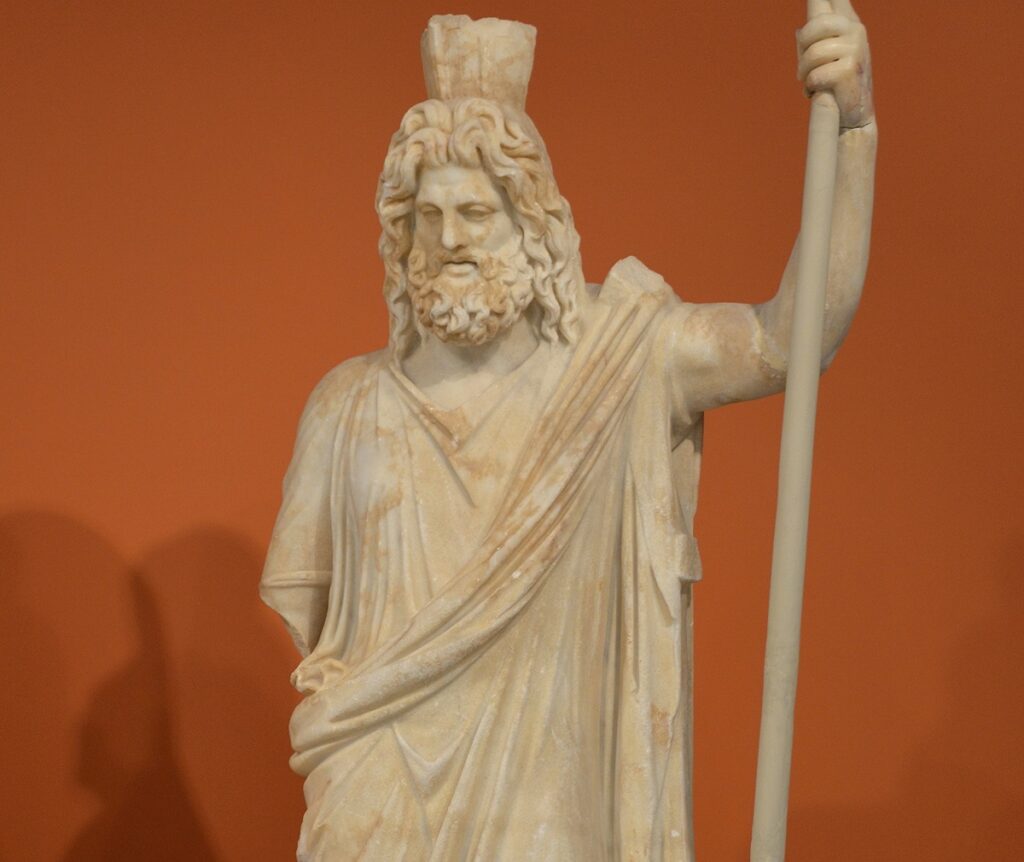

4. Ancient Greek Hades

Ancient Greeks envisioned Hades as the underworld, a shadowy realm ruled by the god Hades, established around 800 BCE. Souls traveled there via the river Styx, ferried by Charon if properly buried and with coins for payment. Hades contained different zones: the Elysian Fields for the virtuous, Tartarus for the wicked, and Asphodel Meadows for ordinary souls. Funerary practices, heroic myths, and literary works like Homer’s epics reveal a culture deeply concerned with moral balance and the journey of the soul, portraying death as both inevitable and structured by divine oversight.

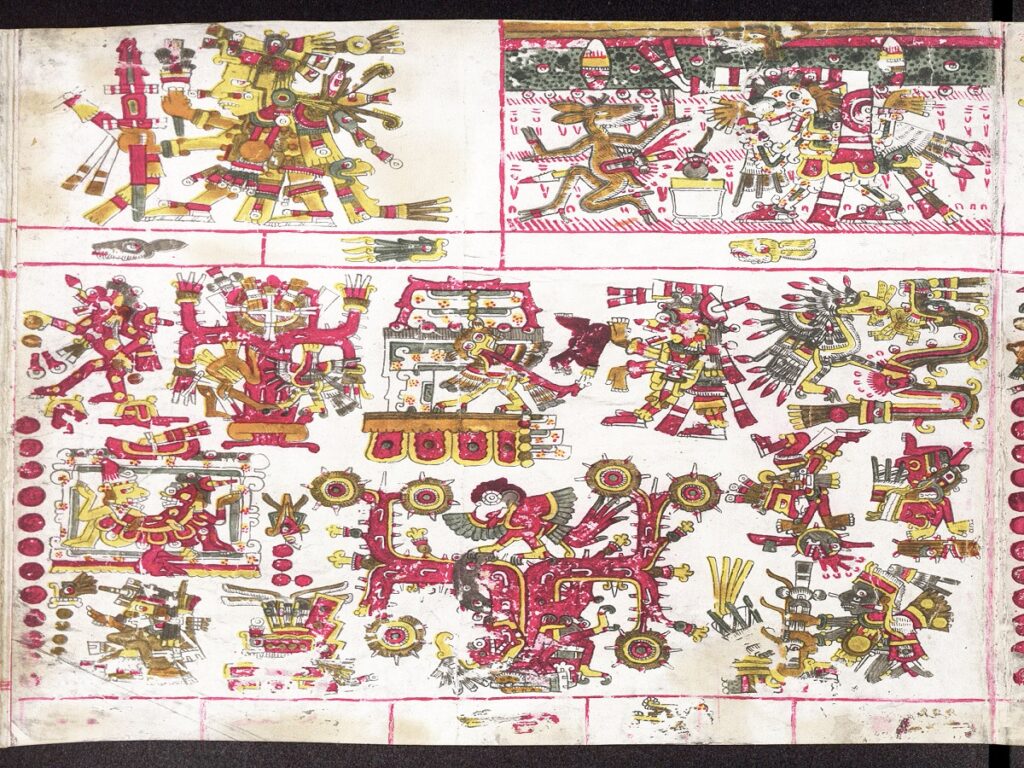

5. Aztec Mictlan

The Aztecs, flourishing from the 14th to 16th centuries CE, believed in Mictlan, an underworld for the deceased. Unlike paradisiacal visions elsewhere, reaching Mictlan required a perilous journey lasting four years, involving trials and obstacles, overseen by the god Mictlantecuhtli. The destination in Mictlan depended less on moral behavior and more on the manner of death; warriors, women who died in childbirth, and others had alternative afterlife destinations. This belief demonstrates the Aztec integration of cosmology, ritual, and societal values, reflecting a practical and challenging vision of the soul’s fate.

6. Maori Spirit World

In Māori culture, originating in New Zealand centuries before European contact, the afterlife is called the spirit world, or “Te Reinga.” Souls’ journey to the ancestral homeland, guided by sacred waterways and landmarks. The departing spirit’s path depends on conduct during life and familial ties, emphasizing communal and ancestral bonds. Rituals, carvings, and chants accompany death, ensuring proper passage and honoring ancestors. Māori beliefs intertwine life and death, suggesting that existence continues in relational and spiritual forms, connecting generations and maintaining harmony between the living and the spiritual realm.

7. Hindu Moksha

Hinduism, established over 3,500 years ago in the Indian subcontinent, centers on the cycle of reincarnation (samsara) and liberation (moksha). The soul, or atman, repeatedly experiences birth, death, and rebirth, influenced by karma accrued in past lives. Achieving moksha ends this cycle, uniting the soul with Brahman, the universal consciousness. Rituals, meditation, and ethical living are pathways toward this release. Unlike linear afterlife concepts, Hinduism views death as transitional, emphasizing spiritual growth and the pursuit of eternal truth, reflecting a holistic philosophy of moral responsibility and cosmic order.

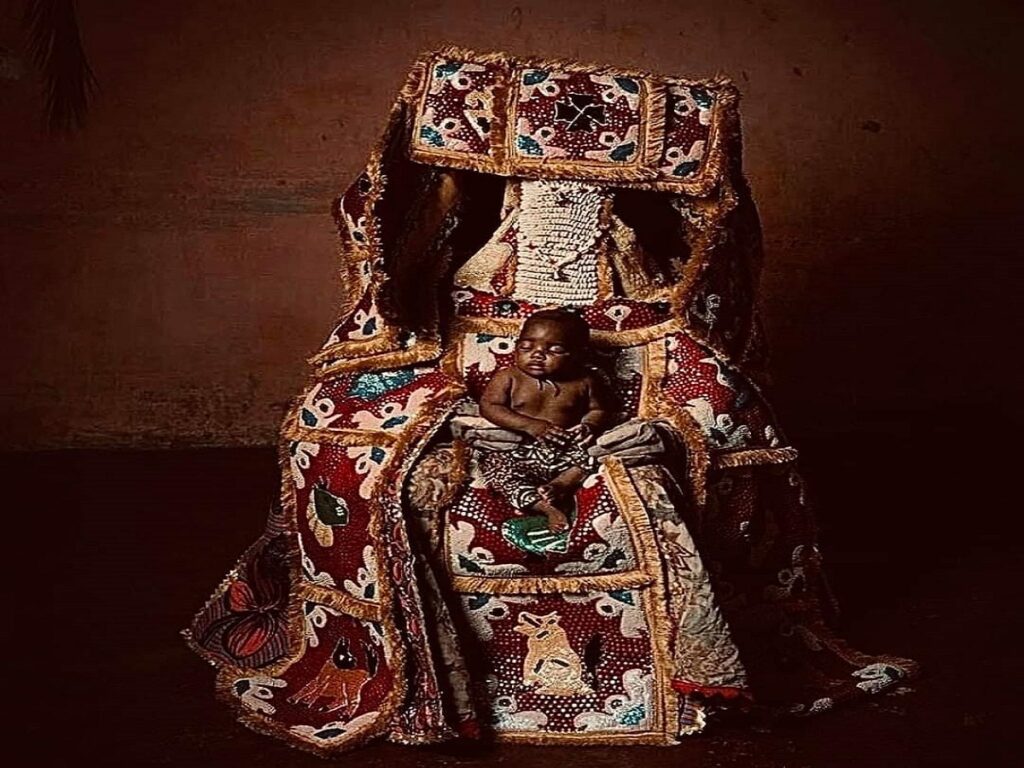

8. Yoruba Orun

The Yoruba people of West Africa, dating back at least to the 1st millennium CE, believe in Orun, a spiritual realm where souls reside after death. Life on Earth is seen as a temporary phase, with the ancestral world offering guidance and protection. Proper funerary rites, offerings, and remembrance maintain harmony between the living and Orun. Souls may reincarnate into the family lineage or remain as protective ancestors. This belief underscores the importance of community, continuity, and respect for ancestors, illustrating an afterlife concept deeply intertwined with social, moral, and spiritual duties.

9. Ancient Chinese Ancestor Realm

Ancient Chinese beliefs, shaped over 2,000 years ago, envisioned an afterlife focused on ancestor veneration. The deceased entered a spiritual realm, where their well-being depended on ongoing rituals and offerings from descendants. Practices like tomb-building, burning joss paper, and seasonal ceremonies ensured ancestors’ favor and continued protection of the living. The afterlife was not seen as a place of reward or punishment but as a continuation of social and familial responsibilities. This worldview reflects a culture emphasizing loyalty, respect, and interconnectedness between the earthly and spiritual planes.

10. Inuit Qilaut

Inuit traditions, developed over centuries in Arctic regions, conceive the afterlife as a continuation in the spiritual world, where souls inhabit places mirroring the living environment. Good hunters and kind individuals join a pleasant realm of abundance, while misdeeds may result in wandering or hardship. Death rituals, including shamanic guidance and communal remembrance, ensure proper passage. The belief system emphasizes balance, respect for nature, and moral behavior. Through these stories and practices, the Inuit maintain harmony between life, death, and the environment, highlighting resilience and reverence in harsh natural landscapes.

Comments