Fabrics have always shaped American industry, style, and safety standards, yet not every material has earned a lasting place in the country’s markets. Some textiles were once celebrated for durability or affordability, only to be outlawed after posing risks that outweighed their usefulness. From toxic fibers to dangerously flammable synthetics, the United States has gradually tightened regulations to protect consumers. The following eight banned fabrics reveal how evolving knowledge and federal oversight pushed them out of circulation.

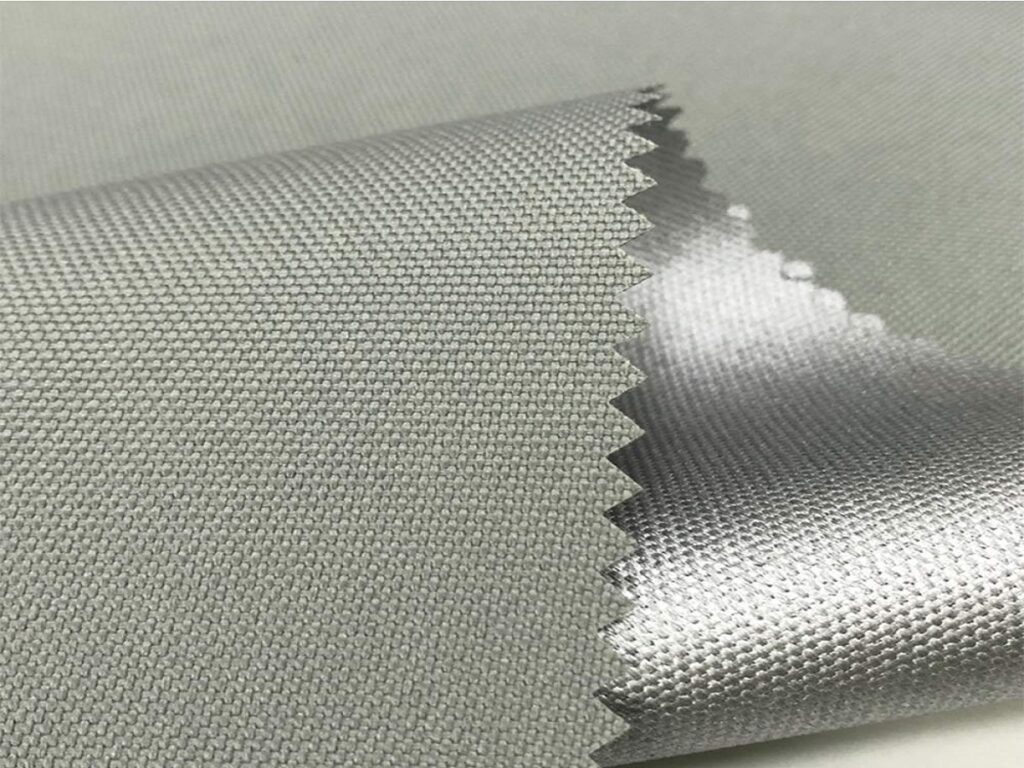

1. Asbestos Fabric

Asbestos fabric was first commercialized in the late 1800s, prized for its heat resistance and used in gloves, protective suits, and stage curtains. Over time, evidence linked its fibers to lung cancer and mesothelioma, prompting growing federal concern. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency moved to restrict most asbestos-containing textiles under the 1989 Partial Ban Rule, which barred new uses in clothing and industrial fabric. Although some legacy materials remain regulated rather than fully erased, asbestos textiles themselves can no longer be manufactured or sold.

2. Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Children’s Sleepwear

PVC-based sleepwear entered American markets in the mid-20th century, valued for low cost and easy molding. But the material released harmful dioxins during production and could emit phthalates linked to developmental risks in children. In 1972, the Consumer Product Safety Commission implemented strict flammability standards that PVC-treated sleepwear consistently failed, leading to its removal from children’s apparel. Later restrictions on phthalates under the 2008 CPSIA reinforced the ban, preventing manufacturers from returning PVC nightwear to U.S. shelves.

3. Chlorinated Tris-Treated Fabric

Chlorinated Tris was introduced in the late 1960s to make children’s pajamas more flame-resistant. Once testing revealed it was a potential carcinogen that could leach from fabric onto skin, scientists sounded alarms about its presence in kids’ sleepwear. In 1977, the CPSC formally banned the chemical’s use in pajamas, effectively outlawing any Tris-treated fabric from being sold in the United States. The decision forced manufacturers to pull millions of garments from stores and remains one of the most decisive chemical-related textile bans.

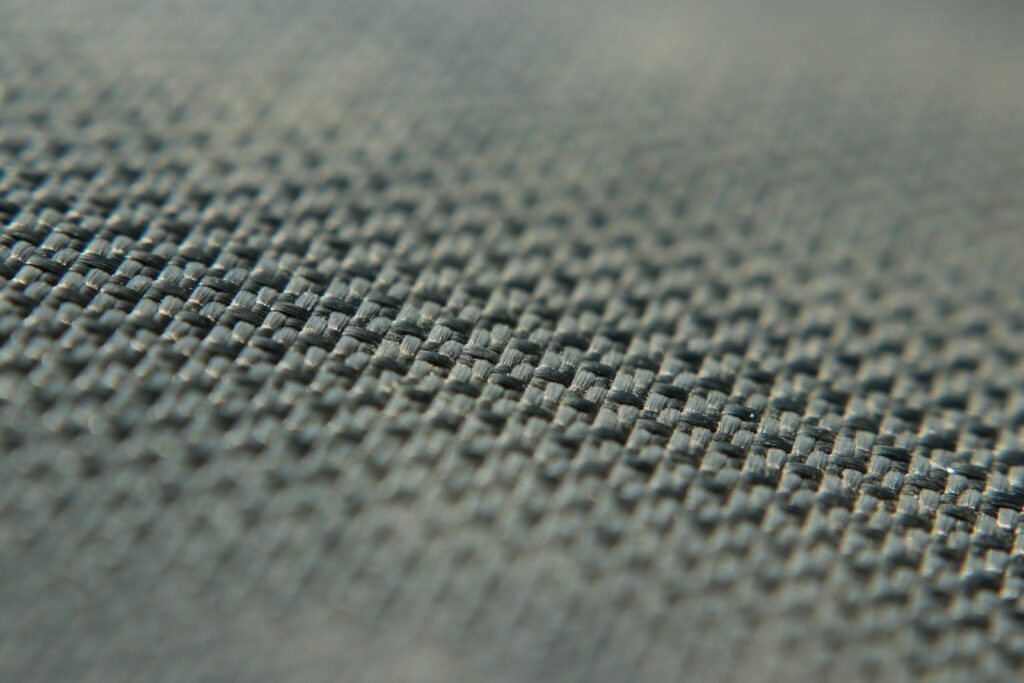

4. Rayon Fabric Made With Carbon Disulfide

Rayon dates back to the 1890s, but earlier U.S. production relied heavily on carbon disulfide, a solvent linked to neurological damage among workers. By the 1960s and 1970s, American labor investigations confirmed the chemicals’ severe health consequences inside textile mills. As regulations strengthened, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration imposed limits that made the older process unviable, leading to its discontinuation. While rayon itself is still legal, the original carbon disulfide–intensive manufacturing method was effectively banned from domestic operations.

5. Polybrominated Biphenyl (PBB)-Treated Upholstery Fabric

PBB-treated fabrics appeared in the 1970s as a flame-retardant option for furniture and public seating. But accidental contamination incidents in Michigan exposed the chemical’s persistence and toxicity, raising concerns that treated upholstery could release hazardous dust over time. In response, the EPA moved to restrict PBBs under the Toxic Substances Control Act, ultimately banning their manufacture and use. As a result, any textile relying on PBB flame retardants disappeared from U.S. production, replaced by safer and more strictly tested alternatives.

6. Certain Polyurethane-Coated Rainwear Materials

Polyurethane-coated fabrics surged in popularity during the 1960s for raincoats and protective outerwear, yet early formulas emitted toluene and other volatile compounds that posed respiratory risks. The CPSC later found that some coatings also failed updated flammability guidelines, creating additional safety concerns. By the early 1980s, federal regulations restricted specific chemical formulations, effectively banning several versions of polyurethane-coated rainwear. Modern variants are permitted, but only those that comply with strict emissions and fire-safety rules mandated by U.S. agencies.

7. Lead-Pigment-Dyed Fabrics

Fabrics colored with lead-based pigments were widely used before safer dyes became standard in the mid-20th century. As health research confirmed lead’s severe neurological effects especially in children regulators moved to eliminate exposure from consumer goods. The 1978 federal ban on lead in paint extended to textiles used in clothing and home décor, removing these dyes from production and sales. Today, any fabric containing lead beyond trace levels violates CPSIA regulations and is barred from entering the American retail market.

8. Halogenated Flame-Retardant–Treated Fabrics in Juvenile Products

Halogenated flame retardants gained traction in the 1980s and 1990s, added to crib liners, carriers, and padded fabrics to meet old flammability standards. Later studies suggested that some compounds could disrupt hormones and accumulate in household dust. The CPSC responded by revising safety rules for infant products, ultimately prohibiting several classes of halogenated chemicals. Although the fabrics themselves were not inherently dangerous, the treatments made them illegal in juvenile items, leading manufacturers to shift toward safer barrier-based fire protection.

Comments